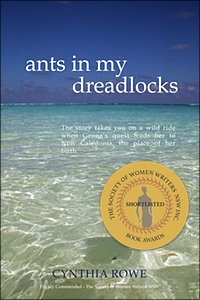

Excerpt from “Ants in My Dreadlocks” © Cynthia Rowe, 2005

My best friend’s mother killed herself by peeing on a hair dryer.

Win—ice-blonde hair duller, skin less perfect than before— yacked about the death a lot. I guess she thought that by shocking people it took some of the hurt away. You know, laughing about your old lady having kangaroos loose in the top paddock, joking about the safety saucepans with the single separate handle you used when you cooked the mush you spooned into her mouth.

She was up-front about Alice’s passing: “The Korsakov’s Syndrome did it. She wouldn’t normally have peed upon a hair dryer.” D’oh. It went without saying that nobody would’ve peed upon a hair dryer. I cringed when I heard Win—into New Age stuff now, meditating and catching the bus into nearby Kingston for Pilates classes—rave about her mum. It was the pits.

Rocked by Alice’s death, too, I deferred my affy year and enrolled at South Central Community College. Which was where I met Clarence (pronounced Clahr-rohnce), my new French teacher. He offered me a work experience stint as English assistante (flash word for assistant) at the Oriel Lycée (flash word for high school) in Nouméa , New Caledonia . Naturally, I grabbed the chance to see the place where I was born. And a sweetener came with it. Oriel Lycée English conversation assistants always holed up together in this yummo mansion.

Sounded kind of cool.

So I was filling in time during the flight from Australia, jotting down a few things about myself. You couldn’t access the Internet from the air, and I’d sworn off chat rooms since a middle-aged codger masquerading as a crater-faced teen tried to come on to me. A bit scary, really.

My long-term life plan was to return to Cairns when my French was up to speed. I’d head for the Northern Beaches, mosey on down to the Amédée Apartments and hang around Sandrine Bas Salaire de Lyon and her partner, Claude, see what I could pick up. I was almost certain Sandrine was my birth mother. (Even though Namilly, the only mum I’d ever known, refused to admit it.) And I knew Sandrine wouldn’t be in Nouméa while I was there. She and her father hadn’t spoken in years—according to Marcel Manet, the guy who claimed I was Sandrine’s natural daughter.

Namilly still wasn’t revealing much.

When I got back to Ravella after my trip to Cairns with Marcel, I expected her to break down and spew out the whole truth about my origins. She didn’t. And it was so frustrating. Instead, she waffled on about our hollow sofa. She said she’d given me two cups of the ‘local drink’—some voodoo thing, I suppose—to knock me out. She told me her heart fluttered in her mouth like crazy as she watched the sofa swing on board and prayed.

So my sofa dreams stopped, knowing Namilly smuggled me to safety inside our hollow sofa during those terrible Events, when violence reigned in New Caledonia , and blood was spilt in the quest for independence.

When I decided to embark upon my work experience programme Namilly told me to keep away from the country of my birth. She shoved her spade into the soil and said, “You won’t like what you find! The only thing you’ll dig up will be sewage, like the contents of that septic tank beneath the canna patch!” Instead of coming to Tullamarine, she stayed brooding in her sunroom kitchen. Said it’d be too painful to watch me jet off to “that place”.

She sniffed a bit.

Namilly’s closeness to Alice used to make me wonder if Win would become my de-facto sister. Well, she did. Sort of. Namilly and Win (fan of rock chick vintage clothes) set up business together only last week. A recycle seconds outlet on the highway, just down from the Zabaglione Woollen Shop—50% of the proceeds to the consignor, 50% to the consignee. No overheads, bar forking out the rent for the shop, it was money for jam they reckoned.

Namilly claimed Re-sale Rose would take everyone’s mind away from “that dreadful dryer incident”.

Stefan Becker and I were an item now. Lots more killer kisses, and not just in his mother’s sunken garden. We’d gone all the way, too. Twice. Responsibly. In the Becker’s bathing box, with rubbers and creams and lying on a fresh white towel. But it was over quickly, and unfulfilling. Had those lowlife bogans who jumped me in the ti-tree bushes affected me that way? Would I feel iffy forever about being touched? But it was great to hear him say “Love ya, mate!” and lie in his arms listening to the waves break on the shore outside.

Stefan had lost his blizzard bubble look a bit. He still wore buckets of zinc cream on his face, but you didn’t get such a nasty surprise when the protection wore off. Apart from a few pit marks, a mega number of freckles and a strange pink thickening of the skin on the tips of his elbows, his psoriasis was unusually clear.

A definite Kurt Cobain look-alike.

Of course, Win didn’t agree. She said she didn’t know how I could stand to touch him. But Elizabeth Stubbs (Fat Betty to everyone but Stefan, and real competition with her newly-acquired, rake thin, dudette body) continued to hang out everywhere my boyfriend went.

Stefan turned eighteen just the other day. His father’s ticker still dicky, there’d been no party, just the promise of a car.

Lately, he’d been making a ginormous number of trips to Kingston—which could’ve been connected with his Nature Shop beside the lube bay of Vince Becker’s service station (you chucked a right past the SWAP ‘N’ GO Cylinder Swap Program sign, then chucked a left past BEST BURNING FIREWOOD). He sold jars of blue ringers, bits of Palaeozoic rocks thrown up from The Cauldron in sealed cellophane packets and marine spiders trapped in sea bubbles. Plus other tat for tourists. Like, crested spoons and stuff.

Since he hauled Namilly out of The Cauldron (she told me she’d slipped but Stef claimed otherwise), they’d become chummy. And it was the first time I’d seen her take an interest in anyone at all of the opposite sex.

The guy in the seat beside me, wearing a gross wedding ring and an even grosser identity bracelet, stuffed the computer printout into his briefcase. The plane plunged from the sea of sooty cloud soup into clear air. I saw him gulp as the cabin shuddered.

And I gulped, too. For I was about to come face-to-face with my French examiner. I went a hectic shade of red as I remembered the boo-boo I made when I stood before monsieur on that fateful day in Ravella Community Hall and used the wrong word for ‘to kiss’. (Fancy telling your examiner Emma Bovary’d gone all the way— which she had, but you didn’t use that word with a total stranger.)

The oral exam wrecked my ENTER score, limiting the courses for which I could apply. So, I accepted this offer…

The plane dropped its wheels for landing.

My stomach twisted as we jerked onto the runway.